The last day of the term meant the handing down of two critical and important opinions.

The first, Department of Commerce v New York, was a blow to the Trump administration. The issue involves the inclusion of a question non the census about citizenship. It was challenged on the grounds that it was arbitrary and capricious — in essence, that it was being used to gather information on undocumented immigrants and not for purposes of the census. In fact, it was argued, it will lead to an inaccurate census count because undocumented immigrants will refuse to take the census at all. The census of course is used not only to determine representation in Congress, but the allocation of funds for pubic health and welfare.

While not holding that the citizenship question was arbitrary and capricious (the legal standard), the court unanimously agreed that the question was “contrived” and served no valid purpose on the census. In other words, the Trump administration’s rationale for including that question -it was needed principally to better enforce the Voting Rights Act — was, in a word, bullshit. ALL the justices saw through it.

Where they disagreed was what to do about. The four judge dissent would have closed the case, but the five judge majority (all conservative) instructed the Department of Commerce to come up with a better reason — one that would pass constitutional muster. In other words, another bite at the apple. Problem is, the census goes to print in literally a few days, and there isn’t time to come up with a better rationale, and fight it in the courts.

Bottom line: the practical result is that the citizenship question will not be on the 2020 census.

But Trump thinks otherwise:

…..United States Supreme Court is given additional information from which it can make a final and decisive decision on this very critical matter. Can anyone really believe that as a great Country, we are not able the ask whether or not someone is a Citizen. Only in America!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) June 27, 2019

Oh, Donnie. You can ask it all you want. Just not in the census (which is supposed to count people, not citizens), and not under penalty of breaking the law.

The Supreme Court also handed down its gerrymandering case — cases, actually.

Rucho v. Common Cause was brought by voting rights groups and Democratic voters, among others, who argued that North Carolina’s 2016 congressional districting plan was unconstitutional, saying the map drawn by Republican legislators amounted to an unconstitutional partisan gerrymander that intentionally diluted the electoral strength of individuals who oppose Republicans.

The other case, Lamone v. Benisek, came from Maryland. A lower court had blocked the map, holding that individuals in the district were retaliated against based on how they had voted, in violation of the First Amendment. This case was brought by seven Republican voters, who argued that then-Democratic Gov. Martin O’Malley, who was overseeing the redistricting process, took particular aim at the state’s 6th congressional district.

The Roberts opinion (for the 5-4 majority, on ideological grounds) ruled NOT that partisan gerrymandering was constitutional, but rather, that it was not a question for the courts. We should at least be grateful that they said THAT, because they could have said, “Look it is OUR decision to make, and we decide that partisan gerrymandering is okay (constitutional)”. Thankfully, they did not.

Roberts essentially wrote, “Hey if we were to decide this case on the law, what would we use as a guideline to say what is permissible and what is not? The laws and the Constitution give us no guideline, so anything we decide would ultimately be a political guess, and that’s not what we do.” Or, as he actually wrote when it comes to partisan gerrymandering, which has been going on in some form or another for centuries, how can a court say “how much is too much?”

He’s not wrong about that, and we should be glad that Roberts does not want it to be an activist Supreme Court — especially a conservative activist one. Frankly, that’s what the Supreme Court *should* have done with Bush v. Gore, where it clearly and *admittedly* did not have a road map or guideline to resolve the case, but it decided to anyway.

On the other hand, Kagan’s dissent is a really good read. In answer to Roberts’ “how much is too much” question, she wrote as follows:

“How about the following for a first-cut answer: THIS much is too much…. A map that without any evident non-partisan districting reason (to the contrary) shifted the composition of a district from 47% Republicans and 36% Democrats to 33% Republicans and 42% Democrats… the largest partisan swing of a congressional district in the country”

(She was talking about the Maryland partisan gerrymandering, but here in North Carolina, it is more widespread, and it favors Republicans)

Kagan gave examples where lower federal courts and state courts were able to say that partisan gerrymandering was “too much” and asked rhetorically, “If they can answer that question, why can’t we?”

And Roberts responds with (essentially) “Yeah, but you still haven’t articulated a rule or guide for the lower courts or the state legislatures who have to draw these lines”.

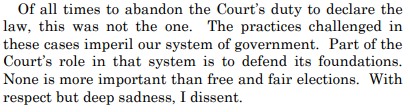

So now we are left with a situation where, certainly in North Carolina and coming soon to a neighborhood near you, the legislature gets to pick the voters, rather than the other way around. As Kagan concluded:

What happens now? Hopefully a move to enact laws and constitutional changes at the state level, and maybe even movement toward a federal constitutional amendment.

And it clearly is a 2020 election issue.

1. Partisan gerrymandering is lawful.

— David Frum (@davidfrum) June 27, 2019

2. Racial gerrymandering is not lawful.

3. Race is among the strongest predictors of partisanship.

4. Square this circle – go!