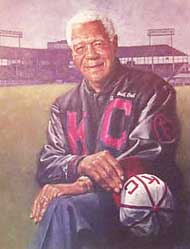

Fans of Ken Burn’s Baseball documentary will be sad to learn that Buck O’Neil passed away:

Buck O’Neil, a star first baseman and manager in the Negro leagues and a pioneering scout and coach in the major leagues who devoted the final decade of his life to chronicling the lost world of black baseball, died last night in Kansas City, Mo. He was 94.

Bob Kendrick, marketing director for the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, reported the death last night, according to The Associated Press. O’Neil entered the hospital in August but was released after a few days. He was readmitted Sept. 17, The Associated Press said.

O’Neil was a smooth fielder and a two-time league-leading hitter with the Kansas City Monarchs, one of the Negro leagues’ most acclaimed teams, and he also managed them. He spent more than three decades working in the Chicago Cubs’ system, becoming one of organized baseball’s first black scouts and then the first black coach in the majors. In all, his baseball career spanned seven decades.

O’Neil had been chairman of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City, Mo., since its founding in 1997 and made scores of appearances to raise funds for it. He bore witness to the exploits of figures like Satchel Paige, Josh Gibson, Buck Leonard, Cool Papa Bell, Oscar Charleston and Ray Dandridge. All of those players were inducted into the Hall of Fame at Cooperstown belatedly, their prime seasons in the Negro leagues coming in the years before Jackie Robinson broke the modern major league color barrier.

O’Neil was among 39 candidates for entry into the Hall of Fame at a special vote in February 2006 to consider figures from black baseball who were not among the 18 previously inducted. Seventeen people were elected in that vote by a 12-person committee, but O’Neil and Minnie Minoso, the only two living figures given consideration, were not chosen.

The Kansas City Star has a nice obit, too:

Buck was the grandson of a slave. He grew up in Sarasota, Fla. — so far south, he used to say, that if he stepped backward he would have been a foreigner. He shined shoes. He worked in the celery fields. He could not attend Sarasota High because he was black.

“Damn,” he said on one particularly hot Florida day in those celery fields, “there’s got to be something better than this.”

“That may have been the first time I ever swore,” he would tell school kids across America. “But it was hot that day, children.”

The lesson of Buck’s story is that there is always something better — but he had to go out and get it. And he did. He played baseball. He was tall and had good reflexes. So he played first base, first for some semi-professional teams and then for the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro Leagues. That, he said, was the time of his life.