Uh no.

Trump arguably got support from the Justice Department on one point. A few days ago, he tweeted that his former lawyer, Michael Cohen, should “serve a full and complete sentence.” This was in response to Cohen’s argument that he should serve no jail time in recognition of his extensive cooperation with prosecutors. It turns out that the Justice Department agrees with Trump on this point—or, at least, part of it does to some extent.

The first surprise of the filings is that the story of Cohen’s cooperation appears to be somewhat more complicated than was apparent from Cohen’s own sentencing memorandum, filed on Nov. 30. There, Cohen’s defense counsel presented their client as having been a very good boy of late—someone who had made mistakes out of excess loyalty to his boss but was working honestly with investigators now in order to turn over a new leaf. In his lawyers’ account, Cohen was all-in on cooperation.

Prosecutors in the Southern District of New York (SDNY) appear to have a somewhat different view of the matter, slamming Cohen’s “rose-colored view of the seriousness of the crimes” and accusing him of having been “motivated by greed” in his criminal actions. More significantly, the memo plays down Cohen’s cooperation, pointing to Cohen’s decision not to enter into a traditional cooperation agreement. Cohen’s lawyers presented this as a move calculated to speed up the sentencing process so their client could more quickly start his life afresh. The SDNY prosecutors, by contrast, describe his having given limited help to prosecutors and see his refusal to enter into a formal cooperation agreement as a reason why he should not reap the benefits of cooperation in the form of a downward departure in sentencing:

His proffer sessions with the [special counsel’s office] aside, Cohen only met with the Office about the participation of others in the campaign finance crimes to which Cohen had already pleaded guilty. Cohen specifically declined to be debriefed on other uncharged criminal conduct, if any, in his past. Cohen further declined to meet with the Office about other areas of investigative interest.

Cohen, the SDNY contends, did not submit to a full debriefing, and his “efforts thus fell well short of cooperation, as that term is properly used in this District.” The SDNY prosecutors are also unimpressed with Cohen’s cooperation with an investigation by the New York State Attorney General, writing that Cohen only corroborated information already known by that office and which he could have been compelled to provide anyway. Notably, in a footnote, the memo flags that Cohen was at one point considering taking the path of full cooperation but chose not to do so.

But the executive branch does not appear to be entirely unitary on this matter, and the special counsel’s office filed a separate brief that has a distinctly friendlier account of Cohen’s cooperation. The two briefs have been harmonized, in the sense that they do not contradict one another or make conflicting sentencing recommendations: The SDNY recommends a “substantial” prison sentence with a “modest” departure from the guidelines range to account for Cohen’s cooperation, while the special counsel’s office recommends that the court give “due consideration” to Cohen’s “significant” assistance and that his sentence for false statements to Congress run concurrently with that of the sentence in the SDNY’s case.

That said, the special counsel’s office describes much more complete cooperation on Cohen’s part in L’Affaire Russe than the SDNY recognizes in matters within its purview and it takes a decidedly warmer tone toward Cohen and his efforts:

The defendant has provided, and has committed to continue to provide, relevant and truthful information to the SCO in an effort to assist with the investigation. The defendant has met with the SCO for seven proffer sessions, many of them lengthy, and continues to make himself available to investigators. His statements beginning with the second meeting with the SCO have been credible, and he has taken care not to overstate his knowledge or the role of others in the conduct under investigation.

As to the substance of the government’s memos in the Cohen cases, they provide little basis for the president’s cries of exoneration. The majority of the information about “Individual-1” presented in the U.S. attorney’s filing is not new. Cohen himself acknowledged it in court and in his original plea documents in August. His own sentencing memo also contains much of the same material.

What makes this document extraordinary is the government’s restatement of the most striking portion of Cohen’s August admissions in its own voice: Cohen indicated that he committed campaign finance violations at the direction of the candidate who conducted an “ultimately successful” campaign for president. The government now echoes this testimony and alleges:

With respect to both payments, Cohen acted with the intent to influence the 2016 presidential election. Cohen coordinated his actions with one or more members of the campaign, including through meetings and phone calls, about the fact, nature, and timing of the payments. In particular, and as Cohen himself has now admitted, with respect to both payments, he acted in coordination with and at the direction of Individual-1.

In short, the Department of Justice, speaking through the acting U.S. attorney for the Southern District of New York, is alleging that the president of the United States coordinated and directed a surrogate to commit a campaign finance violation punishable with time in prison. While the filing does not specify that the president “knowingly and willfully” violated the law, as is required by the statute, this is the first time that the government has alleged in its own voice that President Trump is personally involved in what it considers to be federal offenses.

And it does not hold back in describing the magnitude of those offenses. The memo states that Cohen’s actions, “struck a blow to one of the core goals of the federal campaign finance laws: transparency. While many Americans who desired a particular outcome to the election knocked on doors, toiled at phone banks, or found any number of other legal ways to make their voices heard, Cohen sought to influence the election from the shadows.” His sentence “should reflect the seriousness of Cohen’s brazen violations of the election laws and attempt to counter the public cynicism that may arise when individuals like Cohen act as if the political process belongs to the rich and powerful.”

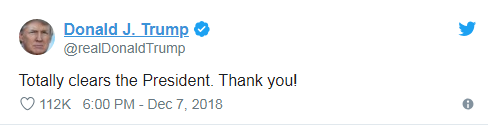

One struggles to see how a document that alleges that such conduct took place at the direction of Individual-1 “totally clears the president.”

In contrast to the SDNY memo, Mueller’s memo contains a fair bit of new information—none of it explosive, but all of it useful in fleshing out the story of L’Affaire Russe. Cohen has clearly given Mueller’s office a great amount of information, and he’s continuing to do so on an ongoing basis. As quoted above, Cohen has met with the special counsel’s office for seven proffer sessions, some of them “lengthy.” And though the sentencing memo states that Cohen lied to investigators in the first session, it emphasizes that Cohen’s statements in every meeting afterward have been “credible.” Mueller states that Cohen has provided information on a handful of Russia-related issues: his own contacts with “Russian interests” during the 2016 presidential campaign; his discussions with others regarding those contacts; other outreach by Russians to the campaign; and, most ambiguously, “certain discrete Russia-related matters core to [the special counsel’s] investigation,” which Mueller writes that Cohen “obtained by virtue of his regular contact with Company executives during the campaign.” (NPR writes that the company in question, a “Manhattan-based real estate company” of which the memo identifies Cohen as an executive vice president, appears to be the Trump Organization.)

In terms of outreach to and from Russians, the memo contains two new data points. First, it states that Cohen “conferred with Individual-1 about contacting the Russian government” about the Trump Tower Moscow project before he actually made contact. From context, the timing of this conversation with Trump appears to have been in the fall of 2015, just when negotiations over Trump Tower Moscow were getting off the ground, though that’s not entirely clear; the memo frames the revelation in relation to a September 2015 radio interview in which Cohen suggested that Trump and Putin might meet during Putin’s visit to the United Nations General Assembly.

Second, it describes a conversation between Cohen and a Russian national “in or around November 2015” in which the Russian “repeatedly proposed a meeting between Individual 1 and the President of Russia” and promised “political synergy” and “synergy on a government level.” The Russian national—who claimed to be a “trusted person” in the country—also told Cohen that, “such a meeting could have a ‘phenomenal’ impact ‘not only in political but in a business dimension as well,’ referring to the Moscow Project, because there is ‘no bigger warranty in any project than consent of [the President of Russia].’” Cohen never followed up with the individual in question, because, as flagged in a footnote, “he was working on the Moscow Project with a different individual who Cohen understood to have his own connections to the Russian government.”

BuzzFeed News reporter Anthony Cormier suggested on Twitter that the Russian man offering “synergy” was likely Russian athlete Dmitry Klokov, whose contacts with the Trump organization Cormier and his colleagues reported in June 2018. Earlier reporting from Cormier and Jason Leopold at BuzzFeed News suggests that the man with whom Cohen was already working on Trump Tower Moscow at the time of the November 2015 phone call was likely Felix Sater: Cormier and Leopold report that Sater began work on the project with Cohen in September 2015.

Perhaps most importantly, the special counsel’s office writes that Cohen provided “relevant and useful information concerning his contacts with persons connected to the White House during the 2017-2018 period.” It’s not clear what these contacts were about and who they were with. But notably, Trump stated in June of 2018 that he had not “spoken to Michael [Cohen] in a long time.”

The government’s submission in the Manafort case is a simpler matter, expanding on the special counsel’s previous allegations that Manafort made false statements to investigators after entering into a formal plea agreement. On multiple occasions during his meetings with the special counsel’s office, the document states, Manafort lied about his interactions with Konstantin Kilimnik, a Ukrainian-Russian citizen whom some reports have linked to Russian military intelligence and whom the special counsel charged alongside Manafort with witness tampering. The special counsel also writes that Manafort lied regarding a wire transfer and, separately, regarding information pertaining to another ongoing Justice Department investigation—about which the document provides no information other than that it is taking place in a jurisdiction other than the District of Columbia.

Finally, as with the Cohen filings, the government’s submission in the Manafort case sheds new light on Manafort’s communications with Trump administration officials. Manafort claimed after signing the plea agreement that he had “no direct or indirect communications with anyone in the Administration,” but according to Mueller, this was yet another misrepresentation of the facts. The government alleges that in a text message exchange in May of 2018, Manafort gave another individual permission to speak with “an Administration official” on Manafort’s behalf. And a “Manafort colleague” claims that Manafort was in communication with a “senior Administration official” up until Feb. of 2018—notably, the month that the special counsel’s office indicted Manafort for a second time in the Eastern District of Virginia.

What should one make of all of this? It has long been clear that the Russian side of L’Affaire Russe involved a long-running, systematic effort to reach out to members of the Trump Organization and the Trump campaign. Mueller’s account of Cohen’s November 2015 conversation about “political synergy” is just one more thread in that pattern. What is less certain is whether and how that Russian effort was reciprocated by those surrounding the president. Friday’s court filings don’t substantially clarify that issue, but they do add more detail and texture to an already troubling picture.

Mueller is still not ready to show his hand on the key substantive questions. But President Trump should should probably go easy on the cries of vindication. They may age badly, and they may do so quickly.