Okay, since I’ve been on an economy/energy blogging tirade today, I think I’ll answer the question on every person’s mind: Why are gas prices so high?

Okay, since I’ve been on an economy/energy blogging tirade today, I think I’ll answer the question on every person’s mind: Why are gas prices so high?

I’ve wondered this myself. Energy and economic aren’t my forte, but I’ve done a lot of reading on it lately, and I think I can boil it down to (admittedly oversimplified) layman’s terms.

The answer is quite simple. Supply and demand. As the demand for something goes up, the supply of it goes down (at least until more of it gets made). And if the supply of something goes down, it become rarer. And when things are rarer, the price goes up.

Example: There’s only one Mona Lisa, and everybody would LOVE to own it. High demand, low supply. And we can’t make anymore. Result? The "price" of the Mona Lisa is "priceless".

Example: There’s only a few hundred first edition copies of "The Velveteen Rabbit", and they’re highly sought by book collectors. High demand, low supply. Price? They’re each worth $10,000 or higher. By contrast, there’s millions of recently-published versions of the "The Velveteen Rabbit". Moderate demand, moderate supply to meet demand. And they’re worth $9.95 at Borders.

Supply and demand. That’s Economic 101. You with me so far? Grasp that and you grasp the rest of this really long post.

So what’s the deal with gas prices?

Well, first of all, let’s consider some things unique to gas, as opposed to, say, grain or some other commodity. Prices for all commodities fluctuate, but gasoline prices are generally more volatile than prices of other goods. Why? Think about it. If grain were explode in price the way gas has, consumers would substitute grain with some other food product. Or go without. Thus, demand for grain would go down. And when demand goes down, prices go down. For grain and most other commodities, it’s self-regulating, in a sense — what goes up in price goes down in demand, which in turn, cause prices to go back down.

Well, first of all, let’s consider some things unique to gas, as opposed to, say, grain or some other commodity. Prices for all commodities fluctuate, but gasoline prices are generally more volatile than prices of other goods. Why? Think about it. If grain were explode in price the way gas has, consumers would substitute grain with some other food product. Or go without. Thus, demand for grain would go down. And when demand goes down, prices go down. For grain and most other commodities, it’s self-regulating, in a sense — what goes up in price goes down in demand, which in turn, cause prices to go back down.

But unlike grain, we can’t substitute gas with something else (or go without). We can’t fill our tanks with something other than gas. I mean, we COMPLAIN, but we still fill our tanks, don’t we? So from a market standpoint, we don’t switch. Which makes it different from grain.

Okay, so what’s the deal with supply and demand viz-a-viz gas?

Well, the supply has been relatively constant over the years. I mean, sure, there have been situational things which cause the supply of crude oil to become scarce. In the 1970’s, the OPEC nations intentionally withheld the supply of gas, allowing it to just sit in the Middle East, in order to create a supply crisis, which drove up prices. That wasn’t very nice. And certainly, conflicts in the Middle East create a strain on the supply of crude oil. But generally speaking, supply has been relatively constant.

The thing that has really changed with gas… is the demand. Let me ‘splain.

The thing that has really changed with gas… is the demand. Let me ‘splain.

You know how gas prices seem to spike up on Memorial Day weekend? That’s because demand is up, compared to supply. That’s a seasonal thing (and there is plenty of that — gas prices are always higher in the summer due to increased demand — more travelling, people using boats, etc.).

But that demand increase is, like I say, a spike. It doesn’t explain the steady increase we’ve seen over the past few years.

No, the kind of demand I’m talking about is something else.

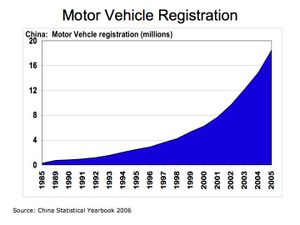

Specifically, it’s this: China and India (especially China) are getting off their scooters, bikes, and rickshaws — and buying cars. This is a phenomenon that really has exploded in the last decade, as capitalism has crept into the Far East.

Now, I don’t know if you’ve heard, but China and India? LOTS of people in those countries. So when they start driving, that’s a heavy demand for gas.

Now, I don’t know if you’ve heard, but China and India? LOTS of people in those countries. So when they start driving, that’s a heavy demand for gas.

Fuel energy, like everything else, takes place in a GLOBAL economy. Don’t think for a second that Exxon, BP, Mobil, etc. are American companies which make the lion’s share of their money off of selling to Americans (or even Europeans). They sell, as they should, do whoever will buy. And if they have lots more customers competing for (roughly) the same supply of fuel, then the gas companies can (and do) raise prices. Economics 101, baby.

You can cynically say that it is greed (and I often do), but actually, it’s just capitalism. It’s just the free market. Exxon is not a charity. It exists to make money, which benefits its shareholders (which may include you, either directly as a stockholder, or indirectly through the mutual funds that you get as part of your 401(k) at work).

So that’s the reason. Gas prices are high primarily because demand, globally, is high. In fact, demand for gas is probably at its highest now because of short term factors (it’s summer, and we want to drive to the ocean and ride our boats), and long term factors (billions and billions of people worldwide are entering the global market of car driving). And it’s the long term factors that will cause prices to continue to rise (just wait until this time next year, kids!)

Not all that complicated. Demand going WAY up, while supplies are not going up to meet the demand.

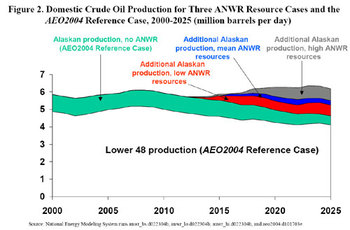

Which beings me back to drilling in ANWR and the coastal regions. Some say, "Well, if we drill in these areas, that will boost supply so that its more commensurate with demand".

Well, yeah, it will increase supply to be more commensurate with demand. But how MUCH more commensurate?

Remember, drilling in ANWR and off the coasts will, by most estimates, only boost the U.S. supply by 2-5%. However, that estimate is based on the assumption that everything pumped from ANWR and the coasts will stay in the U.S.

Remember, drilling in ANWR and off the coasts will, by most estimates, only boost the U.S. supply by 2-5%. However, that estimate is based on the assumption that everything pumped from ANWR and the coasts will stay in the U.S.

But like I said before, the crude oil biz is multi-national. So some, if not most, of that oil drilled is going to end up where the demand is — which (as I said) is in China and India and so on. So a 2-5% increase in supply, small as it is, is even smaller when you understand that it is a mere 0.2% (or whatever) for the global supply.

So, unless Congress passes a law saying that everything pumped within the United States has to stay in the United States, we’re only talking about a savings of a 30 to 50 cents per barrel of oil for ANWR drilling, which translates to a penny or two on the overall gas prices per gallon here and worldwide (since everyone in the world will reap the benefits of ANWR and coastal drilling).

The problem with such a protectionist law? Many things, but mostly:

(1) Assuming the law is constitutional (which is questionable), the mega oil companies will NEVER go for it. They’re going to spend billions drilling in these places, and they aren’t allowed to sell their product to the highest bidder? More likely, they’ll just say, "Oh, well, fuck it then. We’re gonna lose money on this deal if we can’t sell it internationally."

(2) Now, if we DID drill and keep it all at home, we would still have to import foreign oil. Right now, 65% of our oil is imported. Assuming ANWR and coastal drilling is successful, we’ll still have to import, at best, something in the neighborhood of 60%. And how will OPEC respond to a protectionist law like that? Quite likely, they’ll do what they did in the 1970’s, by starting an embargo of their own. So even though we’ll need 60% of their oil instead of 65%, it will be harder to get that 60%. Result? Our prices will actually end up higher as a result than if we had never drilled at all.

Okay, I hear you cry. So what’s the solution?

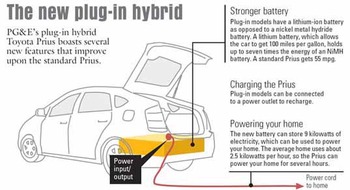

Answer: in the short term, none. In the long term, we have to ween ourselves off of gas dependency. Not just foreign oil/gas, but all oil/gas. Drilling in ANWR and off the coasts simply can’t affect the supply enough to make a difference.

The only thing we can do to make any realistic impact is decrease demand for gas. And you can only decrease demand two ways — (1) tax the living fuck out of gas so people won’t/can’t buy it; or (2) move away from a oil/gas-based energy systtem.

The problems with Option 1, I don’t need to tell you. I’m not talking about a 20 cent increase per gallon, because (I suspect) demand for gas will not go down enough, even if gas is taxed to be $6.00 per gallon. In order to make a REAL difference on demand, gas probably has to be in the area of $10.00 per gallon. Maybe then people will behave differently in their driving and usage habits.

Yeah, I’m not wild about Option 1 either.

So that leaves us with Option 2. The downside to that? It’s going to take time.

So that leaves us with Option 2. The downside to that? It’s going to take time.

But I look at Option 2 this way. We put a man on the moon in less than ten years. When Kennedy proposed doing it in 1960, the materials and technology to put a man on the moon hadn’t been invented yet. Yet, less than ten years later, there was good ol’ Neil planting the flag on the Sea of Tranquilty. If a President were to annouce a serious national effort to develop new (and hopefully clean) technology for running our cars — a national effort along the lines of the Manhatten Project or the NASA Mission to the Moon, that announcement alone would affect the oil and gas commodity markets, and bring some price relief as soon as it was announced. And then of course, when we actually DO ween ourselves off of gas and oil, we won’t give a shit about what the prices are.

Sound reasonable to you?

Now if we can only find a President who will get all Kennedy-esque about this issue. I don’t know if that’s Obama, but it definitely ain’t McCain.